Moscoso's Trail Through Texas

The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 46, October, 1942

Luis de Moscoso Alvarado was a member of Hernando De Soto's expedition to explore La Florida—today's southeastern United States—and to obtain gold and other riches from the native peoples of the North American continent. The army of an estimated 600 men sighted land on May 25, 1539, on the western coast of Florida near what is now Tampa Bay, and landed on May 30. Over the next four years the expedition traveled throughout the southeastern United States. On May 21, 1542, De Soto died from a fever at the Mississippi River in what is now Arkansas; command of the expedition was transferred to Moscoso. The remainder of the journey is commonly known as the Moscoso Expedition. The primary goal of its surviving members was to find an overland route back to New Spain (now Mexico). Many attempts have been made to reconstruct the route of the expedition, nearly all of which bring it into Texas in the summer of 1542.

Scholars have attempted to trace the Moscoso expedition route through Texas mainly with information found in four primary accounts of the journey. A brief version of the army's exploits in La Florida is found in a narrative by the King's factor, Luys Hernández de Biedma, who accompanied Moscoso. This account was written eleven years after the expedition, while Biedma was living in Mexico. Another account is the True Relation of the Hardships Suffered by Governor Fernando de Soto and Certain Portuguese Gentlemen During the Discovery of the Province of Florida. Now Newly Set Forth by a Gentleman of Elvas. This work first appeared in 1557—just fourteen years after the expedition—and was produced anonymously by a Portuguese member of the expedition. A third written source is a romanticized account of the expedition by Garcilaso de la Vega, entitled A History of the Adelantado Hernando de Soto. Garcilaso was not a member of the expedition, and his account was written in the latter part of the sixteenth century and published in 1605. It was based on at least two written and one oral account by expedition members. A fourth account was published in 1851 in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo's Historia general y natural de las Indias. This account was by De Soto's private secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel.

The most exhaustive early attempt to reconstruct the route of the Moscoso expedition, not only in Texas but through the entire southeastern United States, was published in 1939 by the United States De Soto Commission to celebrate the expedition's 400th anniversary. The commission's proposed version of the route through Texas posits that the expedition, led by Moscoso, entered Texas in what is now Shelby County and from there traveled south to a point near San Augustine. It then turned west and went as far as the Navasota River in east central Texas. At this point the soldiers decided that they would not be able to find enough food to feed the expedition if they continued farther west, and thus the Moscoso expedition retraced its route back to the Mississippi River in Arkansas.

In 1942 Rex Strickland used historical, archeological, linguistic, and geographical sources to provide a detailed reconstruction of the army's route through Texas. He suggested that the army entered the state near Texarkana and then moved south along a trail that later became known as Trammel's Trace, until it reached the vicinity of what is now San Augustine. Here the expedition turned westward and traveled as far as the Trinity River. At this point they abandoned their hopes of reaching New Spain by land, and they returned along the same route.

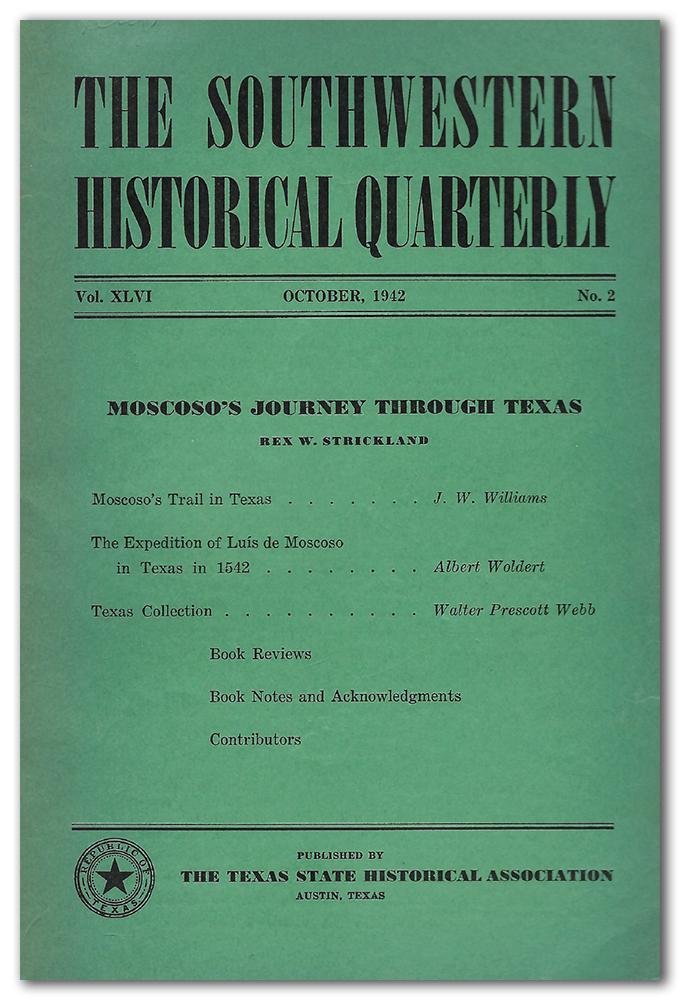

A narrative of Strickland's proposed Moscoso route, along with two other reconstructions—by J. W. Williams and Albert Woldert— were published in the October, 1942 edition of the Southwestern Historical Quarterly. The full text of each of these three reconstructions is provided here.

Later, renewed efforts were made to understand the expedition's route through Texas. Charles Hudson, working in cooperation with the De Soto Trail Study authorized by Congress in 1987, suggested that the army entered Texas from northwestern Louisiana and moved west along Big Cypress Creek; it then turned south and traveled down the Neches River into what is now Angelina County. In his theory the expedition then turned back to the north and finally traveled west, reaching the Trinity River before it abandoned hopes of reaching New Spain overland.

More recently, James Bruseth and Nancy Kenmotsu reconstructed the Moscoso route by relying heavily upon the location of sixteenth-century archeological sites, and, following the lead of Strickland, upon trails that likely existed at the time of the expedition. Bruseth and Kenmotsu bring the army into Texas from Oklahoma. The prominent village site of Naguatex that is mentioned in one of the narratives is argued to have existed along the Red River in what is now Red River or Bowie county. From this point the army traveled south along either Trammel's Trace or the Jonesborough-to-Nacogdoches trail. Both historic roadways connect major prehistoric Caddo Indian villages in East Texas and almost certainly represent prehistoric trails used for many hundreds of years by the Indians. The army moved south to a point near what is now Nacogdoches; turning west it traveled on a trail that later became known as the Old San Antonio Road. The army went as far as the Guadalupe River near the Hill Country but then at this point turned back toward the Mississippi River in Arkansas. During the winter of 1542–43 the Moscoso expedition camped at the Mississippi and constructed boats for a return by water to New Spain. On July 2, 1543, they started down the Mississippi River, and on September 10 some 311 expedition members reached the Pánuco River, which forms the boundary between the states of Veracruz and Tamaulipas, Mexico.

While the expedition failed to find the gold and other riches that similar Spanish explorations had encountered in Central and South America, it did make the first major exploration into the interior of the North American continent and provided some of the earliest observations of Native American peoples, including the Caddo Indians of Texas. Of particular interest is J. W. Williams' reconstruction, which brings Moscoso's expedition to the Caddo villages along what is now known as Village Creek in West Arlington—the same site of the 1841 Battle of Village Creek, led by General Edward H. Tarrant, which resulted in the establishment of Bird's Fort some 300 years after Moscoso's journey.

Moscoso's Journey Through Texas

by Rex W. Strickland

In my doctoral thesis, "Anglo-American Occupation of Northeastern Texas, 1803-1845," I pointed out the necessity for a reexamination of the various hypotheses advanced in the effort to determine the route followed by Luís de Moscoso in the course of his Texas entrada of 1542. This need I emphasized then by saying: "So far as the location of places in Texas is concerned it seems to me that Lewis' notes are faulty." The reference, of course, was to the annotations accompanying "The Narrative of the Expedition of Hernando de Soto, by the Gentleman of Elvas," in Spanish Explorers in the Southern United States, 1528-1542 (edited by F. W. Hodge). More recent study of all available De Soto materials has served only to confirm my earlier impression. Furthermore, my interest in the problem has led me to consider critically the views advanced regarding the Moscoso itinerary in more recent inquiries: viz., Carlos Castañeda's Our Catholic Heritage in Texas, Volume I, Chapter IV; Dr. Robert T. Hill's articles in the Dallas Morning News, 1935-1936 passim; and the Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission. Nor have I been fully convinced of the correctness of the solution of the entrada problem proposed in any of these attempts.

The student of Moscoso's journey in Texas is limited in his inquiry to three sources, none strictly contemporary. Of these the most lengthy, Garcilaso de la Vega's La Florida del Ynca: Historia del adelantado Hernando de Soto, gouernador y capitán general del Reyno de la Florida, y de otros heroicos caualleros Españoles é Indios, is secondary rather than primary, colorful and romantic, but, truth to tell, so obscure and ambiguous that it possesses little historical value. The second is furnished by the True Relation of the Hardships Suffered by Governor Fernando de Soto and Certain Portugese Gentlemen During the Discovery of the Province of Florida. Now newly set forth by a Genteleman of Elvas. Buckingham Smith’s translation is readily available in Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto, edited by E. G. Bourne, or in Spanish Explorers in the Southern United States, 1528-1543, edited by Frederick W. Hodge and Theodore H. Lewis. The Fidalgo of Elvas’ “Relation” has been more aptly rendered into English by James A. Robertson; his translation is found in the Publications of the Florida State Historical Society, II, 11 (1933). Thirdly, we have Luís Hernández de Biedma's "Relation" in the Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto. Unfortunately the concluding part of Rodrigo Ranjel's account of the De Soto expedition is missing, and thus the student of the Texas portion of the entrada loses the benefit of his clear, authoritative narrative. So deprived of Ranjel's notes and skeptical of Garcilaso's obscurantism, we are forced back upon the accounts of Biedma and the Fidalgo, scanty and thin though they may be, in our study of the journey of Moscoso.

An effort will be made here to use every available source of information in an attempt to arrive at warrantable conclusions. Especial attention will be paid to time-place sequence; the Fidalgo has left enough chronological data for us to build up a fairly accurate day-by-day calendar of the progress of the expedition. His descriptions of places are less dependable, but he does not entirely neglect the distance and direction of march. The equation of time-distance data often suggests the more probable of two possible locations. Biedma is to a less degree helpful, though in more than one instance the correlation of his notes with those of the Fidalgo furnishes the key to an apparently insoluble problem.

Linguistic analysis of place and tribal names recorded by the two chroniclers of the expedition provide a further check. It must be granted that the Portuguese and Spanish efforts to reproduce the Indian gutturals are awkward and inapt; yet a study of the words left to us has yielded satisfying results. Interesting probabilities have been suggested—probabilities which in some instances have served to support hypotheses built upon quite dissimilar evidence. It should be emphasized, however, that no identity of a place on the itinerary has been determined by linguistics alone.

Dr. Herbert E. Bolton's scholarly studies of the location of Indian tribes in East Texas in historic times has shed much light on the problem. In every instance, save one, the locations of the sites assigned by him to the several tribes of the Hasinai confederacy fit logically into the time-distance sequence indicated by the relations of the Fidalgo and Biedma. It has not been necessary in any case violently to displace Indian groups from the sites they occupied in historic times in order to justify the route hypothecated in this study. Any conclusions established upon such wishful dispossession must be suspect.

The Fidalgo and Biedma left little evidence that can be substantiated by archaeology, but at least once we have been able to strengthen an otherwise almost unescapable conclusion by resort to the data supplied by Clarence B. Moore's study of aboriginal sites on Red River.1 Pottery serves as well as the written word to tell its story.1Moore, Clarence B., "Some Aboriginal Sites on Red River". Reprint from the Journal of the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia, XIV, 488-644.

The mention of abundance of fish at two places along the way has contributed to fix the probable location of two Indian groups. Climatic conditions have been subjected to inquiry, but with rather meager results. The location of salt springs and salines between the Mississippi and Red Rivers has been studied at length in an effort to determine the route pursued by Moscoso as he marched from the Father of Waters to Texas in the summer of 1542. For this data and for an authoritative study of geologic conditions along Red River in the sixteenth century the student must acknowledge his debt to A. G. Veatch's account of the underground water resources of northern Louisiana and southern Arkansas.22Veatch, A. G., "Geology and Underground Water Resources of Northern Louisiana and Southern Arkansas," United States Geological Survey Professional Papers, No. 46, House Documents, LXVII, 59th Congress, 1st Session. So we have given hostages to history, geography, chronology, linguistics, anthropology, archaeology, zoology, hydrography, and mineralogy in this synthesis. The results have been probable in most instances and certainly logical.

Of the kindred sciences none has proven a more helpful handmaiden of history than geography. The ancient trails of the Caddo and Hasinai are discernible yet to the student who considers the ways of men who hunted salt, food and water. As Archer B. Hulbert points out: "The 'pathless wilderness' is a dearly cherished figment of the American imagination." Never did the explorer or the pioneer forge forward into trackless woods; they were obliged ever to seek out the tracks and trails beat out by the feet of animals and natives in their quest for subsistence. Again, he has said, "the sites of old ferries, . . . will be found to be a reliable guide by which to locate the ancient routes. Infallibly the ferries will mark the strategic points where the ancient trails descended from the high grounds to the fords."3 The ferries, generally, were located at the mouth of a principal tributary of the river to be crossed—the ancient trails followed the same laws of topography as do the highways and railroads of today. Elevation and gradient are natural factors.3Hulbert, Archer B., Soil, Its Influence on the History of the United States, 53.

Guahate and Naguatex

Students of the Moscoso entrada of 1542 are agreed that the Spaniards entered Texas at or near a place which the Fidalgo designated as Naguatex. Indeed, De Soto had heard of the locality while journeying through western Arkansas in the autumn of 1541 but chose to march elsewhither and thus missed Naguatex in person. As the Fidalgo points out:

He dismissed the two caciques of Tulla and Cayas, and set out toward Autiamque. For five days he proceeded through very rough ridges and reached a village called Quipana, where he was unable to capture any Indian because of the roughness of the land and because the town was located among ridges. At night he set an ambush in which two Indians were captured. They said Autiamque was six days' journey away and that another province called Guahate was a week's journey southward—a land plentifully abounding in maize and of much population. But since Autiamque was nearer and more of the Indians mentioned it to him, the governor proceeded on his journey in search of it.44Robertson, James A. (trans.), "True Relation of the Hardships Suffered by Governor Fernando de Soto . . . by a Gentleman of Elvas," in the Publications of the Florida Historical Society, No. 11, II, 201. Robertson's translation will be used throughout this paper. It will be cited simply as Elvas.

October 22, 1541, De Soto came to Quipana, identified by the United States De Soto Expedition Commission as the village whose site is yet discernible near the junction of Antoine Creek and the Little Missouri River, in southeastern Pike County, Arkansas.5 There he rested for a day or two as he considered the way he should turn next in his somewhat aimless journeying. The Indians of Quipana hid in the thickets of the rough, hilly country, and only at length were a few luckless natives captured and put to the question. Two possible ways, they said, were open to the invaders: six days' journey downstream was Autiamque, and a week's travel away to the southward (actually eight days) was Guahate. But since the larger number of Indians spoke of Autiamque, the governor decided to go thither. Thus he let slip his opportunity to visit Guahate.5Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission, 255.

Guahate, in all probability, was none other than Naguatex, to which, as we shall see, Moscoso came in the summer of 1542. This identification rests upon the logic of time and distance. From Quipana (granted that it has been correctly identified as the junction of Antoine Creek and the Little Missouri River) to Autiamque (located by the De Soto Commission in the vicinity of present day Camden, Arkansas) is forty-two miles air line, six days' journey being requisite to cover the distance as it stretched out by the sinuosity of actual marching. Should the same daily rate of march have been maintained from Quipana southward to Guahate for eight days, the distance between the two places as determined by the same process of reasoning was fifty-six miles. Furthermore, if we measure fifty-six miles southward from the mouth of Antoine Creek, our calipers will rest upon Red River some twelve miles south of Garland City, Arkansas. Thus we may conclude that the southern terminus of the Quipana-Guahate trail was near the center, from north to south, of the long famous, fertile Long Prairie, on the east side of Red River, in Lafayette County, Arkansas. The significance of this identification of the location of Guahate becomes apparent when we recall that from time immemorial Long Prairie was associated with the Caddoan culture complex.

Moreover, the application of linguistics to our problem produces logical and satisfactory evidence of the association of Guahate with the Caddoan culture. Let us affix the Caddo gentilic nä- to Guahate; we have Naguahate. This suggests at once that Guahate is nothing more nor less than the Fidalgo's variant for Naguatex. The elision of the "x" (really "ch") sound from Guahate awaits the explanation of a more skilled philologist.

Incidentally, the verbose and obscure Garcilaso de la Vega hints at the identity of Guahate and Naguatex. In a passage quoted by Pichardo, the Inca says:

As it was the beginning of April, of the year 1542, it seemed to the governor that it was time to go ahead with his exploration. Having agreed upon this, he left Utiangue, and took the road for the principal pueblo of the province of Naguatéx, which had the same name, and by it the whole province was called. . . . Passing from Utiangue to Naguatéx, by the route which the Castilians went, there were twenty-two or twenty-three leagues of fertile and very populous country. Our men marched over it in seven days, without anything of note happening to them on the way, except in some narrow places in the woods and arroyos, the Indians came out to make sudden attacks. However, upon our men turning to face them, they took to their heels.

At the end of the seven days they reached the Naguatéx pueblo, found it deserted by its inhabitants, and settled down in it. . . . The governor, having been informed of what was in that province and its vicinity, both by the account of the Indians, and by those of the Spaniards who went to examine the country, left the pueblo of Naguatéx with his army, accompanied by four principal Indians, and led the Castilians into another province. . . . The Spaniards . . . journeyed five days through the province of Naguatéx, and at the end of this time, they reached another called Guancane. . . .66Quoted in Pichardo, Treatise on the Limits of Louisiana and Texas, III, 10.

In the consideration of this passage from Garcilaso, it should be remarked, in the beginning, that his accounts of De Soto's visit to Naguatex in April, 1542, and Moscoso's journey there later in the same year seem to be glosses of the same episode. Inasmuch as the versions of the routes followed by De Soto and Moscoso respectively as furnished by Biedma and the Fidalgo preclude any probability of De Soto's visiting Naguatex, it appears certain that Garcilaso's two confused narratives relate to Moscoso's entrada. Be that as it may, it is interesting to note his statement that "there are twenty-two or twenty-three leagues of very fertile and populous country" between Utiangue and Naguatex. For, if Utiangue (Autiamque) is taken to be Camden, as indicated by the Commission, and Naguatex was located on Long Prairie, as we have assumed, it is fifty-seven miles, as the crow flies, from one to the other. Despite Garcilaso's obscurantism and ambiguity, his startling exactness concerning the distance between the sites assumed to be Autiamque and Naguatex cannot be dismissed lightly. Possibly he possessed some source of accurate information even though he was incapable of weaving it into a creditable synthesis.

We may further fortify our supposition that Guahate and Naguatex were one and the same place by comparing the Fidalgo's statement that Guahate was "a land plentifully abounding in maize and of much population" with his later description of Naguatex as "a region very well populated and well supplied with food."7 The phraseology is reminiscent and the description is apt—for the land of the Caddo was certainly a land of corn and people. This equation of Guahate and Naguatex seems so plausible that it appears strange no previous study of the Moscoso route has mentioned it. For such an identification fixes within the space of a dozen miles the exact point where the Spaniards crossed Red River in 1542.7Elvas, II, 257.

As yet, however, we have not made use of all our available information relative to the identity of Naguatex and Long Prairie. For the probability that the two can be proven to be the same becomes almost a certainty as we apply the data supplied by the Fidalgo and Biedma concerning the Spanish approach to Red River.

Naguatex and the Way Thither

De Soto spent the winter of 1541-42 at Autiamque on the River of Cayas—the town was in the vicinity of present Camden, Arkansas, and the river was the Ouachita.8 The next spring he followed the river down to its juncture with the Mississippi; somewhere there nearby De Soto died on May 21, 1542. Luís de Moscoso was chosen his successor and immediately made preparations to set out westward overland with the design of reaching Mexico. Gauchoya, as the Fidalgo and Biedma called the town where De Soto died, was probably in the neighborhood of Ferriday, Louisiana. This is admitted grudgingly inasmuch as a location farther up the Mississippi and nearer the mouth of the Arkansas, say in the vicinity of Arkansas City, would fit better into our hypothesis as a point of departure; but the Commission’s argument locating Gauchoya near the mouth of the Ouachita seems incontestable.8Final Report, 258.

Monday, June 5, 1542,9 Moscoso and his ragged followers set out from Gauchoya preferring to reach Pánuco by land rather than to try to search for it by sea. Fifteen days later, the Spaniards came to Chaguate, which the Commission maintains was located somewhere in the area now occupied by Price’s and Drake’s Salt Works in Winn Parish. With this conclusion there seems to be no quarrel. While the Fidalgo does not assert that the main village of the province of Chaguate was situated at the salt springs, he does say the Spaniards rested the day before their entry into Chaguate at a small town where salt was made. The cacique of Chuagate, we are told, had visited De Soto at Autiamque in the previous winter.9All dates are in the old style of reckoning; add nine days to correct them to the Gregorian calendar.

At Chuagate, Moscoso was told “that three days’ journey from there was a province called Aguacay.”10 Aguacay, Biedma avers, was due west from Chaguate; if, as the Commission thinks, Aguacay can be identified as the Bistineau Salt Works, near Doyline, Webster Parish, his sense of direction was sadly awry. But until a more plausible location than the Bistineau area can be suggested for Aguacay, it appears to fill most of the conditions set forth by the Fidalgo. For example, he remarks, “There a considerable quantity of salt was made from the sand which they gathered in a vein of earth like slate and which was made as it was made in Cayas.11 A glance back at the salt-making process employed at Cayas shows that there the salt was leached from a blue clay. At the Bistineau Salt Works there is an outcropping of just such cretaceous marl on the shores of Tadpole Lake.1210Elvas, II, 237.

11Ibid, II, 238.

12Veatch, A. G., “Geology and Underground Water Resources of Northern Louisiana and Southern Arkansas,” 30.

Thus far we have agreed with the Commission in its major conclusions concerning the Moscoso itinerary from Gauchoya to Aguacay, though some minor discrepancies may be allowed. But our hypothesis for the journey from Aguacay to Naguatex must vary from the reconstruction projected by the Commission. It assumes the Spaniards marched from Aguacay to Red River and reached that stream in the vicinity of Miller's Bluff, Cedar Bluff or Peru Ferry, all north of Shreveport, but remarks that they must have traveled very slowly. But if we locate Naguatex near the center of Long Prairie, the time-distance sequence becomes more plausible. In the light of this assumption let us delineate the journey as they moved out from Aguacay.

On July 16, "the day the governor left Aguacay he went to sleep near a small town subject to the lord of that province. The camp was pitched quite near a salt marsh and on that evening some salt was made there."13 This was, it appears, not a full day's journey; the shore of the above mentioned Tadpole Lake seems quite satisfactory as the site of the camp where salt was boiled. "Next day [July 17] he went to sleep between two ridges in a forest of open trees;"14 if, as we believe, they were following the old ridge trail between Dorcheat Bayou (the northern tributary of Lake Bistineau) and Bayou Bodeau, the open grove between two ridges was somewhere northwest of Minden, Louisiana. "Next day [July 18] he reached a small town called Pato;"15 Pato is shown on the "De Soto" map between confluent streams, which may very well have been Dorcheat Bayou and Bayou Bodcau. Really, at present, the two streams do not join before their junction with Red River but the cartographer was not obliged to be informed of such geographic niceties. Pato, then, let us assume, was somewhere between Cotton Valley and Serepta. "The fourth day [July 19] after he left Aguacay, he reached the first settlement of a province called Amaye."16 The "De Soto" map depicts Amaye as lying between Bayou Bodcau and Red River. In consideration of the distance covered and the direction of march, we may conjecture that Amaye was situated somewhere in the vicinity of Arkana, Arkansas, near the south end of the Long Prairie.13Elvas, II, 238.

14Ibid, II, 238.

15Ibid, II, 239.

16Ibid, II, 239.

This assumption is strengthened by the statement that Naguatex was a day and a half's journey from Amaye—i. e., perhaps fifteen to twenty miles at their average rate of march.

On July 20, Moscoso left Amaye and camped at noon on the edge of a luxuriant grove, standing isolated in the prairie. There the Spaniards were attacked by the combined bands of the men of Amaye, Hacanac and Naguatex, whom they successfully beat off. They remained on the scene of battle that night and the next day (July 21) they reached the habitations of the Naguatex on the east bank of a river (Red River); though the chief of the Naguatex, they were told, lived on the opposite side of the stream.

Naguatex and Its People

The day was not yet spent and Moscoso marched down to the very bank of the river; the opposite shore, it was observed, was occupied by many Indians awaiting the invaders. The leader, not knowing the strength of the aborigines, the location of the fords, nor, indeed, the depth of the river, did not attempt to force a passage; instead he drew back a quarter of a league (just about two-thirds of a mile) and camped there "in an open forest of luxuriant and lofty trees near a brook."1717Elvas, II, 242.

Moscoso had reached the ancient habitat of the Caddoan confederacy, whose several constituent tribes and sub-tribes dwelt along Red River on either side from the mouth of Sulphur River as far upstream as the Spanish Bluffs in present day Bowie County, Texas. As we have seen, the Fidalgo mentions certain of the groups encountered by Moscoso, namely, the Amaye, the Hacanac and the Naguatex; he assigns the predominant place among these to the Naguatex. His omission of the Kadohadacho from his list renders rather improbable Lewis' conclusion that the Spaniards crossed the river as far northward as the White Oak Shoals, north of Texarkana. Obviously there is no reason to identify any of the three groups of Indians mentioned as the Kadohadacho, i. e., the Caddo "proper." Rather it seems we should take a clue from Father Douay, who visited the region of the Great Bend of Red River in 1687. He says:

This tribe [Kadohadacho] is on the bank of a large river, on which lie three more famous nations, the Natchoos, the Nachites, and the Ouidiches, where we were very hospitably received.1818"Douay's Narrative," in Cox, I. J. (ed.), Journeys of La Salle, I, 251.

Or we should glance at the lists of tribes furnished by his companion, Henri Joutel, who notes:

. . . Before our departure we were informed that the villages belonging to our hosts, being four in number, all allied together, were called Assony, Nath-osos, Nachitos and Cadodaquio.1919"Joutel's Historical Journal of Monsieur De La Salle's Last Voyage to Discover the River Mississippi," in Cox, I. J. (ed.), Journeys of La Salle, II, 178.

Tonty, who came to the land of the Kadohadacho in 1690 in search of La Salle, observes:

The Cadadoquis are united with two other villages called Natchitoches and Nasoui, situated on Red River. All nations of this tribe speak the same language.2020Memoir, by Sieur de la Tonty," Ibid., I, 45.

A study of these observations leads us to two or three conclusions worthy of credit: first, in the late 1600's the Kadohadacho (to use the terminology adopted by the Handbook of American Indians) were the predominant tribe of the Caddoan confederacy; secondly, associated with them were the Natchitoch, the Nanatscho and the Nasoni. The presence of the Natchitoch and the Nasoni in the great bend region of Red River has been a source of confusion to many students who forget that these two tribes were divided in historic times into the "upper" and "lower" Natchitoch and the Red River and Angelina Nasoni.

Only Douay, it will be marked, mentioned the Ouidiches as resident upon Red River in 1687, though both Joutel and Tonty record the presence of Naouidiche or Naouadiche farther south in the land of the Hasinai. Indeed Bolton proves beyond doubt that the Naouidiche and the Nabedache were variant names of the same tribe who dwelt in 1687 on San Pedro Creek, west of the Neches.21 The archaic name of the tribe, Gatschet says, was Nawadishe, from witish, 'salt'; therefore, they were the "people of salt." All of which comes to but one fact: the Ouidiches of Red River were not the same as the Naouidiche (Nabedache) of the Neches. In default of any other witness than Douay to the presence of the Ouidiche upon Red River, one is inclined to assume that he misplaced them through a forgivable lapse in recollection.21Handbook of American Indians, II, 1.

Thus, while one hesitates to disagree with so eminent an authority as Swanton, his equation of Naguatex and Ouidiche seems unjustified. Taking a clue from Gatschet, he identifies Naguatex as nawidish, "place of salt;"22 in his notes on Indian names, however, he renders the Caddoan word nawadish.23 Even so, this is not a very satisfactory transliteration of the Caddo word that the Fidalgo was endeavoring to reproduce; let us suppose instead that he was attempting to approximate syllables which sounded to his ears näwitash. Näwi means in Caddo "below" or "down there;"24 tash is the familiar term written elsewhere techás, i. e., "friends," or, more technically, "allies."25 Thus conceivably Naguatex was näwitash, "friends down there." But down where? Surely downstream from the main Kadohadacho village, which was located, in historic times at least, on the river above present day Fulton. Down there just where we should expect to find the Naguatex in their villages on Long Prairie. Perhaps it would not be too bold to suggest a possible connection between the Naguatex and the later Nachites (Upper Natchitoch) of Douay's account.22Final Report, 53.

23Ibid., 61.

24Mooney, "Caddo and Associated Tribes," Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

25Handbook of American Indians, II, 738.

The Amaye were clearly Caddoan, taking their name from amay, "man." Whether they can be recognized as any specific one of the historic Red River tribes is debatable. As for the Hacanac—if the Fidalgo originally spelled the word with the Portuguese "s" we should have azanaz, i. e., Nasoni. This conjecture is lent some color of support by a notation on the "De Soto" map which shows a village by the name of Aznauz, though it is located far south of the region commonly allotted to the Hacanac.

Surely we must seek for Naguatex on Red River. With our problem thus delimited, we have but to search out a locale that fills the conditions adduced by the Fidalgo in order to determine its exact location. First, we must look for a populous, fertile region inhabited by a confederacy of kindred folk, living on either side of the river; secondly, this large, aboriginal population must possess the ability to produce a superior sort of pottery. For the Fidalgo has not neglected to observe that, "Pottery is made there little differing from that of Estermez or Montemor."26 The presence of extensive aboriginal settlements in Lafayette and Miller Counties, Arkansas, is abundantly attested not only by the accounts of early explorers but by archaeological evidence from many mound sites clustered on either bank of the river from the mouth of the Sulphur Fork up to Dooley's Ferry. Indeed, in no other Red River section are the remains quite so prevalent save near the mouth of the stream. Concerning the pottery taken from the southwest Arkansas mounds, Clarence B. Moore observes that its makers paid much attention to the ceramic art—even cooking vessels were exquisitely modeled and profusely decorated.26Elvas, II, 257.

Three sites warrant especial attention. Taken in order as we ascend the river are the Haley Place, the Battle Place, and the Foster Place. The Haley Place mounds are on the west bank of Red River, just north of its juncture with the Sulphur Fork; Moore rated this site as the most notable he studied in Arkansas because of its extent, having both domiciliary and burial mounds. The Battle Place mounds are located in Lafayette County, four or five miles below Garland City but on the opposite side of the river; they are on the shore of Battle Lake, an old bed of the river; they are noteworthy not only for the size of the principal mound but because the Battle Place site is in close proximity to the Harrell and Cabinas Place mounds on the east side of the river and has the McClure Place site just across the river in Miller County. The Foster Place mounds are situated just south of the Hempstead-Lafayette County boundary; the site furnishes a pottery, a fine polished black ware, of higher average excellence than any found elsewhere on Red River, except possibly that discovered at Gahagan far south in the vicinity of Coushatti.2727Moore, Clarence B., Some Aboriginal Sites on Red River. Reprint from the Journal of the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia, XIV, 483-644.

In view of the size of the mound at the Battle Place, its proximity to other sites both on the east and west side of the river, together with the cumulative evidence furnished by the study of time-distance sequence, it appears that no other place in the Long Prairie area has a better claim to be identified as the village of the Naguatex on the left bank of Red River. The village at the Haley Place may well be one of the Naguatex habitations of the right bank; the "De Soto" map shows Naguatex just so located between the Sulphur Fork and Red River at the junction of the two streams. The Foster Place site represents a town of kindred folk, whose identity must remain indeterminate.

Moscoso remained quietly at his camp on the east bank of the river until the tenth day after his arrival. On the morning of July 31, he sent out two parties of horsemen, each guided by Indians, to seek out the fords up and down the river. The scouting parties, though opposed by hostiles, succeeded in getting across to the opposite side, where they found extensive habitations and much food; they, however, returned at evening to the camp on the east bank of the river.

A day or two later Moscoso sent an Indian courier to inform the cacique of Naguatex that if he did not come in and receive pardon he would inflict upon him the chastisement he deserved for his perfidy. The day after the emissary's departure he returned with a message that the chief would visit the Spaniard the next day; thus it would appear, from the time needed to go and come from the chief's village, that the principal town of the Naguatex was located at the distance of a day's journey from Moscoso's camp. The day following the messenger's return (August 3 or 4) an embassy of natives came to visit Moscoso to discover his mood; seemingly reassured, they returned to their chief, who came in two hours later. The cacique and his retinue presented themselves to Moscoso, as the Fidalgo remarks, "all weeping after the manner of Tula which lay to the east not very far from that place."28 The chief emphasized his humility in a speech which laid the blame for his intransigence upon a brother who had been killed in the battle of July 20. Moscoso granted his pardon to the supplicant.28Elvas, II, 244.

Four days later (August 8) Moscoso set forth upon his way, that is, he marched out from his camp in the grove. "But on reaching the river he could not cross, as it had swollen greatly."29 Robertson's rendering of the Fidalgo's account makes it clear that the freshet-filled stream was the one in front of the camp and not another as Buckingham Smith's awkward translation has led some students to believe. Balked by the high water, "the governor returned to the place where he had been during the preceding days."3029Ibid., II, 245.

30Ibid., II, 246.

Eight days after (August 16) Moscoso's first attempt to cross the river, he set out again and "passed to the other side and found a village without any people."31 Profiting by former experiences, Moscoso did not trust himself in the deserted village where he would be liable to ambush but camped in the open fields. He demanded guides of the chief of the Naguatex, who neither came himself nor sent the assistance asked; after some days, Moscoso sent scouting parties up and down the river to burn the towns and seize captives. Both objectives were attained so effectively that the cacique sent six principal men and three guides "who knew the language of the region ahead where the governor was about to go."3231Elvas, II, 246.

32Ibid., II, 247.

Inasmuch as Moscoso had lingered some days in the land of the Naguatex on the west bank of the river, it may be assumed that he used up the major portion of a week, let us say five days. Thus it was not until August 22 that he was ready to resume his journey. He had loitered first and last for a full month plus a day or two more in the neighborhood of Naguatex. All this we find in the True Relation of the Fidalgo, since Biedma neglects entirely the episodes connected with Naguatex.

Biedma, however, in speaking of Aguacay (where Moscoso had stopped on his way to Naguatex), interjects one illuminating comment:

. . . After leaving this place [Aguacay], the Indians told us we should see no more settlements unless we went down in a southwest-and-by-south direction, where we should find large towns and food; that in the courses we asked about, there were some large sandy wastes, without any people and subsistence whatever.3333Biedma, "Relation," Bourne (ed.), Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto, II, 36.

Thus Moscoso's inquiries concerning the ways thence from Naguatex had elicited the reply that westward there were but sterile, unpeopled areas. To the natives used to the lush productiveness of the river bottom fields such must have seemed the open Black Prairies westward with their interspersed mottes of blackjack and post oak. Neither sterile nor sandy to us, to the Caddo they were lands of deer and the buffalo, scarcely fitted for corn; if the Spaniards sought towns and people they must journey southwestward. The men of Naguatex knew the speech of the natives in that direction and well they might, for the language of the Caddo and Hasinai differed little. Westward along Red River the explorers could only expect to meet the wandering Tonkawas and Kichai who spoke "barbaroi" and find lands whose inhabitants were not acquainted with even the primitive hoe culture of the Caddo.

Nor were there trails toward the west. In my long study of the area between the Red River and Sulphur Fork, I have found no evidence of an aboriginal ridge trail, though it is reasonable to suppose that there must have been a hunting path along the divide. But to the southwest there had led since the time when the memory of man ran not to the contrary the trail from the land of the Caddo to the habitations of their kinsmen, the Hasinai of the East Texas pinelands.

Through East Texas

The heat of summer was now heavy upon the steaming bottoms of Red River; on August 22, Moscoso departed from the vacant fields of Naguatex on this side of the river, moving, as Biedma makes evident, southwest-and-by-south. Surely he was following the ancient road from Red River to the Hasinai.

At the end of the third day (August 24), he "reached a town of four or five houses, belonging to the cacique of that miserable province, called Nissohone." Students of the entrada have correlated Nissohone —Nisione, in Biedma's spelling — with the Nasoni who in later years were living some thirty miles north of Nacogdoches on the headwaters of an eastern branch of the Angelina River, but they forget that in 1687 the "Upper" Nasoni were resident on Red River. It seems safe to assume that the Nissohone of the Fidalgo were a small village group of the Red River Nasoni, living poorly and miserably apart from the main tribe on the river. The three days' march requisite to cover the distance from Naguatex combined with the Fidalgo's observation that theirs was a poor region, thinly peopled and producing scant corn, suggests that Moscoso had reached the sandy upland west of Atlanta somewhere near the junction of Cherry Branch and John's Creek. To this proposal one objection can be offered: travelling at their average rate of march (eight to eleven miles per day), the Spaniards could scarcely have covered the distance between Naguatex and the Nasoni camp in three days. But it must be remembered that they had guides familiar with the country, that they were following a well-defined road and that their horses were rested by the long stay at Naguatex.

The Fidalgo continues:

. . . Two days later, the guides who were guiding the governor, if they had to go toward the west, guided them toward the east, and sometimes they went through dense forests, wandering off the road. The governor ordered them hanged from a tree and an Indian woman, who had been captured at Nissohone, guided him, and he went back to look for the road. Two days later, he reached another wretched land, called Lacane.3434Elvas, II, 247.

Two things are clearly indicated by this passage. The Spaniards wished to follow a well-known trail or road, and the native guides (those who had come with them from Naguatex?) sought to lead them away from it to the eastward. The trail could hardly have been any other than the ridge road that led southward along the divide between Jim's Bayou on the east and Black Cypress Bayou on the west down to the famous crossing on Big Cypress, in the environs of Jefferson. Their guides were attempting to entangle their unwelcomed guests in the thickly timbered bottoms of the creeks tributary to Red River. Only after Moscoso had hanged the recreant guides and employed the services of a captive Nasoni woman did he find the road which brought him four days after his departure from the Nasoni village to another "wretched land called Lacane." They arrived there in the afternoon of August 28. Lacono should be equated with Nacono perhaps, though the De Soto Commission's surmise that the Nacao are meant cannot be disregarded, nor should we overlook the possibility that Lacane and Nacaniche may be the same. In any case, these three tribes, Nacono, Nacno and Naconiche, lived to the northeast of all the Hasinai,35 though in historic times, at least, none was located as far north as the 82nd parallel. Despite this apparent contradiction, it seems probable in consideration of our time direction data that the Lacane village (waiving all ethnic identifications) was situated somewhere in present day Harrison County alongside the old Caddo path that bent crescent-wise east of Marshall to reach the Sabine at the point where the Rusk-Panola County boundary line now touches the river.35Final Report, 276.

At Lacane, an Indian was captured and questioned concerning the country beyond. The luckless captive told of the land of Nondacao, populous, with its houses scattered about the fields as was the custom of the Hasinai, and productive of much corn. Its cacique, being summoned in advance by Moscoso, came to meet the governor with weeping as had the chief of the Naguatex. Especially significant is the Fidalgo's statement that the Indians presented the invaders with an abundance of fish; Nondacao was undoubtedly close to a stream of some importance. Immediately the Sabine comes to mind. Considering the direction and distance traveled since they had left Naguatex, it seems fairly certain that they had reached one of the ancient Anadarko (for Nondacao is equated with Anadarko) villages south of the Sabine. Two such towns existed there in historic times: an upper in the northern part of Panola County36 and a lower on the East Fork of the Angelina River in the extreme southern part of Rusk County. The Fidalgo does not mention the time requisite to go from Lacane to Nondacao but if we glance ahead it will be seen that the Spaniards spent five days on the road from Nondacao to Aays. If we measure back from San Augustine (which we will accept tentatively as the site of Aays) we find the distance to the old Caddo crossing on the Sabine to be a little less than seventy miles, too great a distance to be covered in five days at their customary leisurely pace. From the Rusk County Anadarko site to San Augustine is more nearly fifty miles, or just about the distance ordinarily covered in five days. The abundance of fish offered the invaders at Nondacao argues rather for the Panola County site. The De Soto Commission may offer the solution in its hypothesis that the Indians of East Texas moved gradually southwestward between 1542 and 1690;37 in which case the Anadarko met by Moscoso may have been living on the headwaters of Attoyac Bayou where Shelby, Rusk and Panola Counties meet. One day at the least and three days at the most would have been sufficient to reach the various Anadarko sites discussed; let us accept the median and allow two days' march. Therefore, Moscoso probably reached Nondacao on the afternoon of August 30.36Bolton, "Native Tribes About East Texas Missions," in Southwestern Historical Quarterly, XI, 268.

37Final Report, 277; map, 348.

From Nondacao Moscoso sought to reach Soacatino (Xacatin, according to Biedma's variant); Soacatino breaks down into two Caddo words, Scho-atino, or, perhaps more properly, Sha-atino. In either case, we have Red Hills or Red Mounds. As near as our meager evidence ever approaches certainty, we have here a geographic term for an area long later appropriately named by the white settlers the Redlands. Of course Redlands (Soacatino, Red Hills) is a generic term and we have no way to determine definitely the exact village which the natives particularized as Soacatino. But the four Indian mounds once discernible in the north portion of Nacogdoches give evidence of an aboriginal village.

But the guide conscripted at Nondacao played the usual game and led the group out of the way to the eastward. After five days they came to Aays (Hais is Biedma's spelling) somewhere in the neighborhood of present day San Augustine. There they were attacked by the natives who sallied forth, exclaiming, "Kill the cows—they are coming." Inasmuch as it was September 4 (September 13 new style), the Indians may well have expected the southward migration of the buffalo; certainly they assumed that the horses, with which they were not familiar, were a strange sort of bison. The hostility shown by the Aays (Hais) was quite in character; the Eyeish, with whom we must identify them, long maintained their reputation as a perverse and contentious folk. Moscoso defeated the natives after a sharp fight and marched into their town. In the fighting the Indians suffered heavy losses; no Spaniard was seriously wounded though men and horses incurred some slight injuries.

The length of the stay at Aays (Hais) is not indicated by the Fidalgo or Biedma; Garcilasso, always suspect, says two days. If we accept his reckoning, they left Aays on the morning of September 7; three days after their departure they reached Soacatino, their journey having been lengthened by the ruse of their guide (a native of Nondacao), who, as usual, sought to lead them off the road. By highway the distance from San Angustine to Nacogdoches today is thirty-five miles, an interval which at the slow pace of the Spaniards would have required three days' march. If, as we surmise, Soacatino is an awkward attempt to render scho-atino (sha-atino), there can be little doubt that the adventurers found Soacatino among the Redlands of the East Texas Pine forests; Xuacatino, Biedma observes, lay amid close forests. For our purposes the four ancient mounds on the approximate site of present Nacogdoches was the Soacatino of the Fidalgo.

To retrace briefly, on the day they left Aays (Hais) their guide, a man of Nondacao, informed them that his people had heard that the Indians of Soacatino had seen other Christians. Moscoso, on his arrival at Soacatino, inquired anxiously if this rumor was true. No, the Indians replied, they had not actually seen the white men but they had heard it said that they were traveling about near somewhat to the south. Biedma adds his recollection of the report, saying, "Hence the Indians guided us eastward to other small towns, poorly off for food, having said that they would take us where there were other Christians like us, which afterward proved false." His statement that the Indians led them eastward, from which direction they had just come, has confused most students of the entrada; obviously through an error in transcription the phrase al este has been substituted for al oeste —the Indians really guided them westward. Westward to the site of the Hainai village on the east side of the Angelina where later, in 1716, was established the mission of Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción.

Most commentators have either chosen to discredit altogether the rumors concerning the other Christians or have elected to build upon them a problematic account of the proximity of Coronado. Especially have a few made use of the approach of other white men to prove that Moscoso ascended Red River far enough westward to meet with natives who had seen or heard of Coronado. More reasonably, it seems, we may assume that the people of Soacatino had heard of Christians, who surely were not members of the Coronado expedition but rather Cabeza de Vaca and his associates. Cabeza had traded inland from Galveston Island in 1530-31 to a distance of thirty or forty leagues;38 he had not gone as far north as the Redlands but the rumor of his presence to the southward had doubtless passed from tribe to tribe until it came to the land of the Hasinai.38Hodge, F. W. (ed.), "The Narrative of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca," in Spanish Explorers in Southern United States, 1528-1543, 56.

Here we should pause to establish our time sequence as definitely as possible. First, let us recall that Moscoso left Aays (Hais) on the morning of September 7 and reached Soacatino in three days' marches—thus he reached Soacatino in the afternoon of September 9. Thence he went to the site of the village afterward occupied by the Hainai; thence he turned and traveled for "about six days in a direction south and southwest," where he halted. So says Biedma. Presumably he had reached Guasco at the time he came to a temporary stop. If we assume he left Soacatino on the morrow of his arrival there, he set forth on September 10, and used x days in reaching Hainai (two days should suffice), bringing him to the evening of September 11; add six more days required to reach Guasco and we have September 18. Singular confirmation of this date is found in a statement of the Fidalgo:

. . . He marched for twenty days through a poorly populated region where they endured great need and suffering; for the little maize the Indians had they hid in the forests and buried it where, after being well tired out with marching, the Spaniards went trailing it, at the end of the day's journey looking for what they must eat. On reaching a province called Guasco, they found maize with which they loaded the horses and the Indians whom they were taking.3939Elvas, II, 250-251.

The puzzle presented by the statement that "he marched for twenty days through a poorly populated region where they endured great need and suffering" before he came to Guasco may be solved by adopting the Commission's suggestion, "this 20 may include part of the preceding itinerary."40 If we count back twenty days from September 18 (our tentative date for the arrival at Guasco) we have August 30; further inquiry shows they probably arrived at Nondacao on that day. A rereading of the Fidalgo's account will reveal further that he had insisted upon the poverty of the country since their departure from Nondacao, although he had recorded that "the land of Nondacao was a very populous region, . . . and there was an abundance of maize."41 But we have not exhausted our time data; they camped in the vicinity of Guasco for four days, certainly, and perhaps a day or two more; after which they went ten days' journey to the River Daycao, from whence they decided to retrace their steps eastward, "for it was already the beginning of October."42 And so it was according to our reconstruction of the time-sequence; quite probably they turned back from Daycao during the first week of October. Thus if we are right in our time-sequence hypothesis—and it cannot be in error more than two or three days—Moscoso came to Guasco either on September 18 or 19.40Final Report, 333.

41Elvas, II, 247, 248.

42Elvas, II, 254.

To reach Guasco, Biedma says they marched for six days in a direction south and southwest. The journey thither from the small town poorly off for food (which we have agreed was the village later occupied by the Hainai, if, indeed they were not resident there in 1542) was accomplished slowly and deviously. Their guides as usual were treacherous and the country through which they were marching afforded little food.

The location of Guasco lies at the very heart of the entrada problem; thus we need to use every available scrap of evidence to determine the place's identity. Guasco, we note first of all, was not a town but a province or region; secondly, it was fertile and productive of much corn. All of which argues for an area populated by a number of Indian groups, sedentary in their customs and essentially agricultural in their life. At once, the distance traveled, the direction followed and the nature of the folk found at the end of the march suggests Guasco should be identified as the ancient habitat of the Hasinai which spanned the Neches River to include the vicinity occupied at present by Alto and Weches. Although the De Soto Commission spent some effort in an attempt to identify Guasco as a variant Caddoan name for a tribe of that people, possibly the Yscani,43 the answer seems simpler and clearer.43Final Report, 278.

Guasco is the Fidalgo's rendition of the Caddoan word wäscho. The element scho is familiar to students of Caddo linguistics; it means "hill" or "mound." The term is variously reproduced by early travelers as scha, sco or scho and in Mooney's modern glossary as sha.44 In the Representation of the Missionary Fathers, 1716, the Neche are termed the Nascha45—it needs no great imagination to find in this word the Caddoan dissyllable na-scha, i. e., "people of the hill," specifically, of course, the people of the great mounds southwest of present day Alto. But Guasco may be equated with wa-scho, or better still, näwä-scho, if we add the gentilie nd-. The presumption that Guasco and Nascha are the same appears too strong to dismiss as mere coincidence. Until a more plausible solution is advanced, it seems we are justified in identifying Guasco as the land of the Neche, if not the very village occupied by that folk in historic times.44Mooney, "The Caddo and Associated Tribes," in the Fourteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1103.

45Handbook of American Indians, II, 50.

But we have further conjectures to offer in support of our identification of Guasco inasmuch as "thence they went to another village called Naquiscoca."46 Some students of the entrada problem have suggested that Naquiscoca is recognizable as Nacogdoches, partially, we suspect, because the Nacogdoches are better known than other more obscure members of the Hasinai confederacy. The correlation is not impossible, of course, but a scrutiny of the Fidalgo's appellative, Naquiscoca, reveals the presence of three Caddoan elements which may be rendered näwi-scho-cha, a phrase which quite probably can be translated "lower hill place." The old Nabedache village on San Pedro Creek across the Neches River from the land of the Neche fits the description.46Elvas, II, 251.

At Naquiscoca the Indians at first denied that they had heard of other Christians but when their memories were sharpened by torture the natives said that they (the Christians) had reached "another domain ahead called Nacacahoz and had returned thence toward the west whence they had come."47 Moscoso moved on to Nacacahoz, spending two days on the way; there a captive Indian woman told a fantastic story of her capture by white men from whom she had subsequently escaped. To ascertain the truth of her story, Moscoso sent a party of horsemen, guided by the woman, to search out the place of her supposed capture. After the party had gone three or four leagues the woman confessed that she had lied; "and so they considered what the other Indians had said about having seen Christians in the land of Florida."48 Having found the land about Nacacahoz poor in corn, they returned to Guasco.47Ibid., II, 251.

48Ibid., II, 252.

Who were the Nacacahoz thus introduced, somewhat casually, into our story? Some have seen in them the well-known Natchitoches,49 but more reasonably it appears that Nacacahoz is the Fidalgo's attempt to render Nacachau, which had as its variants Nacachao and Nacachas.50 But in 1716 the Nacachau were living on the east side of the Neches River just north of the Neche; if they were resident there in 1542 they do not fit into our scheme very clearly. But if the Nacacahoz of the Fidalgo could be identified as the Nechaui, who were living, according to Peña's diary,51 some five and a half leagues southeast of the old crossing between the Neche and the Nabedache in 1721, then we have settled the Guasco-Naquiscoca-Nacacahoz problem. To sum up briefly: Moscoso reached Guasco (Nascha, Neche), southwest of the present site of Alto, September 18 or 19; thence he went across the Neches River to the village of the Nabedache near Weches; from there he journeyed somewhat southeast to the village of the Nechaui, a distance of about fourteen or fifteen miles, in search of other white men. A scouting party failed to find any evidence of other Christians thereabout, if indeed the rumor of their presence was not just a lie served up to please the Spaniards. From Nacacahoz, as we have previously stated, the weary adventurers returned to Guasco.49Handbook of American Indians, II, 37.

50Ibid., II, 4.

51Ibid., II, 49.

There "the Indians told them that ten days' journey thence toward the west was a river called Daycao where they sometimes went to hunt in the mountains and to kill deer; that on the other side of it they had seen people, but did not know what village it was."52 Much thought and not a few guesses have been devoted to the identity of the River Daycao. Of one thing we can be certain: it was beyond the land of the agricultural Hasinai. Furthermore, ordinarily a ten days' journey would enable them to cover approximately a hundred miles, but their rate of march had declined to nearer six or seven miles per day. Again, though the Fidalgo says that Daycao was toward the westward (but he does not say due westward), Biedma indicates the direction pursued was rather toward the southwest. This time-direction datum, without the aid of further evidence which will be brought to bear on the problem, suggests that the River Daycao was the Trinity. If they moved along the old hunting path from the Neches to the Trinity, approximating the later Camino Real, they reached the Trinity somewhere in southwestern Houston County. In no instance could they have gone as far west as the Brazos—time did not permit.52Ibid., II, 252.

Here it should be explained that the Caddo word for "river" was a nasalized vocable which the Fidalgo rendered cao and Joutel transliterated into French as cano, ex., Canohatino, Red River.53 Nor should we overlook the established fact that in very early times the Bidai Indians were located just south of the famous crossing of the Old Spanish Road on the Trinity. It is not known definitely by what name these Indians designated themselves; bidai is a Caddo word meaning "brushwood."54 Tribal traditions asserted that the Bidai were the oldest inhabitants of the area, and, though surrounded by the Caddo, at least in later times, they remained aloof and retained their independence. Daycao, therefore, was the Caddo designation for the river west of their principal habitat; it meant "River of the Bidai," or, in its shortened form, "Brushy River." Persons acquainted with the natural features of the Trinity bottoms can testify to the accuracy of the descriptive appellation.53Handbook of American Indians, I, 653.

54Ibid., I, 145.

A cursory reading of their accounts may give the impression that the Fidalgo and Biedma are not in accord concerning the course of events involved in the march from Guasco to Daycao and their sojourn at the latter place. The Fidalgo implies that the Spaniards moved as a unit from Guasco to the east bank of the River Daycao, whence Moscoso sent a few horsemen to explore the opposite side, but they went westward only a few miles at the most. Biedma, on the other hand, says that a party of ten mounted on swift horses went farther to see if maize could be found; they traveled for eight or nine days and found a wretched folk without houses but living in huts, subsisting on fish and flesh. But a careful comparison of our two sources suggests a reasonable explanation of the apparent differences in the accounts.

Let us examine Biedma's narrative first; he says:

Thence [i. e., from Guasco] we sent ten men on swift horses to travel in eight or nine days as far as possible, and see if any town could be found where we might re-supply ourselves with maize, to enable us to pursue our journey. They went as far as they could go, and came upon some poor people without houses, having wretched huts into which they withdrew; and they neither planted nor gathered anything, but lived entirely upon fish and flesh. Three or four of them, whose tongue no one we could find understood, were brought back. Reflecting that we had lost our interpreter, that we found nothing to eat, that the maize we brought upon our back was failing, and it seemed impossible that so many people could cross a country so poor, we determined to return to the town where the Governor Soto died, . . .5555Bourne, ed., "Relation of the Conquest of Florida presented by Luis Hernández de Biedma" in Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto, II, 37.

Place over against this the Fidalgo's account:

There [i. e., at Guasco] the Christians took what maize they found and could carry and after marching ten days through an unpeopled region reached the river of which the Indians had spoken. Ten of horse, whom the governor had sent on ahead,56 crossed over to the other side, and went along the road leading to the river. They came upon an encampment of Indians who were living in very small huts. As soon as they saw them, they took to flight, abandoning their possessions, all of which were wretchedness and poverty. The land was so poor, that among them all, they did not find half an ‘alquire’ of maize. Those of horse captured two Indians and returned with them to the river where the governor was awaiting them. They continued to question them in order to learn from them the population to the westward, but there was no Indian in the camp who understood their language.5756Italics mine.

57Elvas, II, 252-253.

From the two passages, often thought contradictory, we can reconstruct the movement of the Spaniards westward from Guasco substantially as follows. Moscoso selected ten horsemen to ride in advance of the main force for some days (not necessarily eight or nine days) while he followed more slowly with the remainder of his army, who were obliged to adjust their pace to that of the foot soldiers and bearers carrying corn on their backs. Ten days were thus used up in reaching the Daycao. Meanwhile the scouts, who had ridden ahead, reached the river, crossed over to the west side, captured two to four of the unfortunate natives and returned to join the governor at his camp. The reconnoitering party reported the poverty of the country across the stream. Its miserable folk lived in huts (both Biedma and the Fidalgo emphasized the wretchedness of the dwellings); nor could the captives speak a tongue intelligible to Moscoso's Hasinai guides. They had reached at last the westernmost terminus of their fruitless Odyssey. Disheartened by the unfavorable report of their scouts and faced by the lateness of the season, for it was the beginning of October, they decided it was the better part of judgment to return eastward to the Great River from whence they had come.

So far as the evidence, specific and cumulative, can be brought to bear on the problem it indicates that Moscoso had reached the Trinity River in what is now southwestern Houston County, Texas. Perhaps the camp was located some miles south of the old crossing, long afterward known as Robbins' Ferry, opposite the mouth of Bedias Creek, today the boundary between Walker and Madison Counties. How long the Spaniards remained there does not appear in the record, but only a few days at the most; thence they turned back along the way they had come. As they retreated they began to repent their folly in despoiling the Indian villages on the outward march and it was only when they returned to Naguatex that they found the houses rebuilt and filled with corn. From Naguatex they pressed on to Guachoya, whence the next year they went to Mexico. But that segment of their adventure does not belong to our story of Moscoso's journey through Texas in 1542.5858The notes of of Theodore H. Lewis reconstructing Moscoso's route according to his hypothesis will be found appended to "The Narrative of the Expedition of Hernando de Soto, by the Gentleman of Elvas" in Spanish Explorers in the Southern United States, 1528-1542. His notes are quoted, and my comments are set off in italics. He located Aguacay on the west bank of the Quachita River, two miles south of Arkadelphia, in Clark County, Arkansas. The attack by the chiefs of Naguatex, Hacanac and Amaye occurred "probably on the Prairie de Roane, near Hope." The small river upon which they camped the next day (inedentally the small river existed only in Lewis' misreading of Buckingham Smith's faulty translation) was "Little River in Hempstead County." The place where they crossed Red River was "about three miles east of the line between Texas and Arkansas, in the latter state, and is known as White Oak Shoals." At that point, Lewis thought he saw just such an island as the one upon which Pato is shown on the De Soto map. But Pato was on the thither bank of Red River, not on this side. This is "in the elbow or ‘great bend' of Red River, and is about forty miles long, and from two to thirteen miles wide. At the upper end of the island and just south of the ford, is an overflowed piece of land known as the Bench Farm, which is the property of Mrs. Edna L. Orr. It was here that Moscoso and his followers camped for several days. This is the only large island above Fulton on Red River, and the next ford, forty miles above by land, is too far up." Lewis has Moscoso camping on the wrong side of the river. Lewis disregards Nisione, Lacane, and Nondacao completely, but locates Aays (Hais) "to the southward of Gainesville, Texas, the town being located just west of the 'Lower Cross Timbers,' on the prairie." (He fails to state his reasons for placing Aays just there.) Soacatino, he asserts, was in the Upper Cross Timbers in the vicinity of Wichita Falls. Guasco he places in Palo Pinto or Young County and identifies with the name Waco, linguistically an almost impossible equation. He thinks the Naquiscoca was the tribe known to the Spaniards as the Naquis and to the French as the Haquis. He does not mention the Nacacahoz. Now comes the return to Guasco and the trip to the river Daycao, which he identifies as the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos. The Indians captured on the other side of the river were Comanches. The southward migration of the Comanche probably had not reached Texas in 1542. "The point at which they probably stopped was at the south angle of the river, in the northwestern part of Fisher County, distant about 100 miles from the fort." There, of course, they turned back to Naguatex. This hypothesis overlooks the logic of time and distance entirely; from the White Oak Shoals to Wichita Falls, thence to Young County, to Naquiscoca (not definitely located by Lewis), and then out to the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos is roughly four hundred and twenty-five miles air line. This distance had to be covered in forty-three or forty-five days, since it is fairly evident that Moscoso left Naguatex August 23 and reached Daycao at the beginning of October (say October 6). Such a rate of march was not impossible, granted that the invaders were constantly on the move, which they were not. The Fidalgo states that the distance from Naguatex to Daycao, whatever route was followed, was approximately two hundred and sixty-five miles, i. e., three hundred and ten from Aguacay to Daycao, less about forty-five miles. Finally, we cannot, except by the most radical dislocation of Indian groups, conceive of the Nasoni, Anadarko, Eye-ish and other Hasinai confederates living in the upper Red River-Brazos region in 1542.

Dr. Robert T. Hill's reconstruction of the Moscoso route may be found in the Dallas Morning News, September 1, 1935, March 29 and October 4, 1936. Substantially he outlined the itinerary as follows: from Bowie County westward up Red River as far as Spanish Fort in Montague County, where he placed Soacatino. Thence twenty days southward to Guasco, identified as modern Waco, then to Navasota (his Naquiscoca), thence back to Guasco and from there out to the juncture of the Concho and Colorado in the vicinity of Paint Rock. One needs only to say that the distances covered by such a march would have been impossible within the time limits set by the Fidalgo.

One or two further observations, indicative rather than confirmatory of the validity of conclusions reached in this account concerning the route pursued by Moscoso, should be offered here. First, much has been said by the exponents of the Red River route about the sterility of the soil and the dryness of the climate in the area traversed by Moscoso. The commentators forget that summer was upon the land: the heat of August and September had dried the corn brown in the fields, the dusty-gray leaves of the oak hung intermingled with the drooping needles of the pine, the cicada droned constantly throughout the drowsy day, and above all, a copperas sky—surely one who knows the drought of summer in East Texas will not need the semi-aridity of the Grand Prairie to provide the stage for Moscoso's entrada.

For the summer of 1542 was droughty; the Fidalgo expresses the amazement of the Spaniards at finding Red River running at flood stage when rain had not fallen for weeks in the vicinity of their crossing. Thereafter, throughout their journey, they passed through a country that had not had rain for some time prior to their coming. This may and perhaps does account for the chroniclers' failure to mention the crossing of the rivers they found-the Sulphur Fork, the Sabine, the Angelina and the Neches. Certainly, a century and a half later Joutel and Douay, who traveled over the Texas portion of the route in reverse direction, but in spring and not in summer, had occasion to note the presence of all four streams.

Moscoso's Trail in Texas

by J. W. Williams

Seeming now as if they had come from the pages of an ancient story book, a party of Spanish adventurers, headed by Luys de Moscoso, made the first entrada of Europeans into the northeast corner of Texas just four hundred years ago. To connect the journey of these archaic figures—some of whom were clad in the armor of medieval knights—with the Southwest of today presents a field for no little interesting speculation. An attempt to follow the actual route of these Spaniards, which is the chief problem of this paper, holds some of the intriguing aspects of dragging a bit of mythology into the plain daylight of Texas history. A brief review of the background of the expedition will prove helpful.111Edward Gaylord Bourne, Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Florida, as told by a Knight of Elvas and in a relation by Luys Hernández de Biedma (2 vols.; New York, 1904). Hereafter cited as Bourne, De Soto. The introduction to this article is based chiefly on these narratives.

The expedition originated in Spain under the official stamp of the king, and included several persons of noble birth, chief of whom was the leader of the party, Hernando de Soto. With a will of iron, and courage that knew no fear, De Soto conducted his party from Spain to Cuba, from Cuba to Florida, and from there across most of the area that is now the southern United States. His long-drawn-out journey was, in the main, a search for gold. With his curiosity in microscopic focus looking for that precious element, he crossed the present states of Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas,2 Missouri, and probably parts of Kansas and Oklahoma. After three years of such wandering, De Soto turned back to the mouth of the Arkansas. Somewhat broken in spirit, he sickened and died, leaving his followers to work out their own salvation.2Herbert E. Bolton, The Spanish Borderlands (New Haven, 1921), 69.

Indian fights and long exposure had taken a toll of nearly half of his six hundred men, and only about forty of his two hundred and forty horses still survived.3 The search for gold had proved to be a disappointment; these men who had been fired by visions of immense riches had worn out their European clothes and were now dressed in the skins of animals.4 Probably their morale had suffered as much as their raiment.3Bolton, The Spanish Borderlands, 69.

4Bourne, De Soto, I, 214.

After De Soto's death the luxury-loving Moscoso was selected as leader. After due consultation with the ranking Spaniards of the group, he decided to turn the course of travel toward the settlements in Mexico. Thus the frayed-out remnant of the well trimmed De Soto expedition came into the land that we now know as Texas. Slowed to a snail's pace by the lack of horses and further impeded by a train of captured Indian slaves and burden-bearers, the party was able to travel little more than an average of six miles per day.5 For four months this strange party of white and red-skinned humanity moved westward and southwestward under the convoy of the few mounted men who still faintly resembled Spanish cavalry. Then fear seized them, fear of starvation if they went ahead, and the party returned to the mouth of the Arkansas, hoping to escape by water.5A study of the actual time traveled from the mouth of the Arkansas to the river Daycao (Bourne, De Soto, I, 166-180) reveals that about seventy days were so spent. This does not include the detour at Guasco. Accepting the estimate of 150 leagues (Bourne, De Soto, I, 182) as something near the correct distance traversed in those seventy days, the result is an average near six miles per day.

But details of the journey are not the purpose of this paper. Chiefly, this effort is concerned with the route which the Moscoso party followed in Texas. Difficult as that task may be, the writer has employed evidence not previously emphasized in attempting its solution.

To begin the search for a trail at the very end of it is an odd, and doubtless novel procedure, but that is the method to be employed in this research. Like raveling an old stocking by beginning at the toe, that journey of four hundred years ago seems easier to understand when first approached from the "wrong end." Here, at the final point of that long, crooked trail—on the bank of some Texas river—this unique party of Spaniards gave up the idea of crossing the North American continent by land. That stream beside which Moscoso's party stood in early October, 1542, most authorities believe, was the Brazos, but agreement ends just there. As to the exact place on that great river, those same authorities disagree by half the width of Texas.